This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

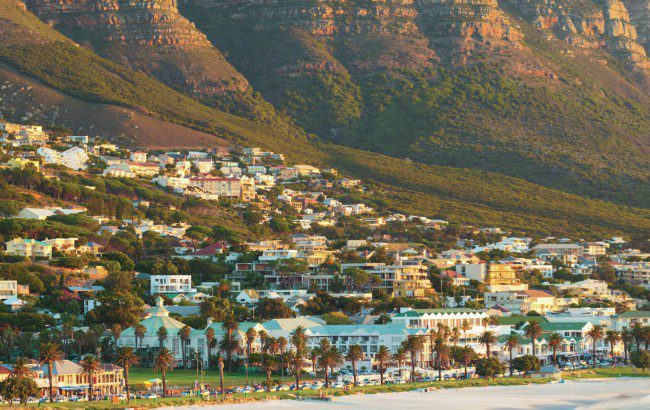

South Africa: the post-pandemic rebound

By Tom Bruce-GardyneSouth Africa’s stop-start approach to selling alcohol during the pandemic played havoc with the country’s drinks trade. We explore what last effect this has had on the nation’s spirits trade.

*This feature was originally published in the March 2023 edition of The Spirits Business magazine.

As Scotch whisky celebrated smashing through the £6 billion (US$6.2bn) barrier in exports last year, more than £1bn greater than its previous record in 2019, South Africa made a modest contribution to that success. Its imports of Scotch rose by a third in value to £103 million on the previous year and by 15% in volume to 3m cases.

Yet both figures are still below what was achieved in 2019. As with all spirits, the recovery from the pandemic remains a work in progress. Given how hard hit the sector was in South Africa, that is probably not surprising.

Christelle Reade‐Jahn, director of the South African Brandy Association, vividly recalls the progression of events in 2020. “There was a complete lockdown for three weeks that was extended to five weeks, and then the shocker – that all alcohol sales would be prohibited,” she says.

“What happened in South Africa was unique. We pulled together to form an alcohol‐industry working group, and presented 12 examples of prohibition around the world to the government that showed that nowhere did they actually work.”

Psychological toll

There were three periods of prohibition that year, totalling around 20 weeks, culminating in a final ban three days after Christmas that lasted until 1 February 2021. The domestic alcohol drinks industry was reported to have lost R25bn (£1.16bn) and around 120,000 jobs as a result. As IWSR Drinks Market Analysis reported, that last ban “took a fatal psychological toll on a consumer whose confidence was already knocked by a tanking economy, 34% unemployment rate, a disastrous vaccine rollout, and general pandemic fatigue”.

“If you look at most drinks categories they have recovered pretty well,” says Reade‐Jahn. “There was obvious pantry stocking after Covid, and probably over‐purchasing due to the mindset of the government.” Restrictions and bans came in with such little warning, that consumers learned to pounce quickly. “People were thinking, ‘Instead of two bottles, I’ll buy a case of Klipdrift’,” she says referring to the country’s top‐selling brandy, owned by Distell. “These huge changes in the way people purchase obviously create supply chain issues.”

While panic buying has eased since 2021, Junior Jekwa, Distell’s marketing cluster lead: brandy and liqueurs, says: “One of the biggest scars and challenges from the pandemic has been the constraints in raw materials, like glass and cans shortages, as well an increase in the costs of goods. Economic inequality is a major challenge for South Africa, but the Covid pandemic elevated this, both in reducing consumers’ disposable income with lost jobs, and the increasing cost of living.

“We’ve seen during and after the pandemic that South Africans have doubled down on trusted brands and value. We are fortunate our brands offer both. That said, the brandy category is under pressure, and needs to be rejuvenated among a new, younger, and inclusive consumer. While brandy and coke is the staple serve, other categories have grown through experimentation, and by the expansion of new serves, broadening their usage of mixers and cocktails.”

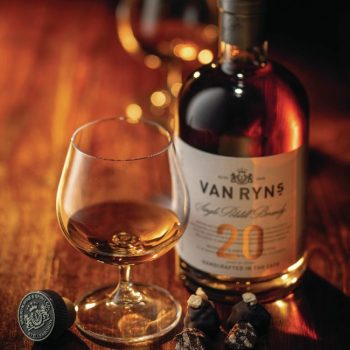

As of 2020, brandy was the third biggest spirits category in South Africa, on 2.6m cases, of which just 7% was Cognac and Armagnac, according to the IWSR. It was just ahead of vodka, on 2.4m cases, though behind whisky on 2.9m, which, for thefirst time, had been overtaken by gin on 3.2m, up from 2.7m the year before. These four accounted for 88% of all spirits.

Distell’s Jekwa says: “Over 2022 we’ve seen sales normalise and return to pre‐Covid levels.” In its full‐year results to last June, the company’s revenue in South Africa rose by 24.4%, with volume up by 18.7%. In September, South Africa’s Competition Commission approved Heineken’s €2.2bn (US$2.3bn) bid for a 65% share of the business, although this does not include its Scotch brands, such as Scottish Leader and Bunnahabhain.

Distell is also a leading player in South African whisky, which has “had a very strong run since 2020, with double‐digit growth in a declining category”, says Dino D’Araujo, who looks after the company’s whisky, gin and vodka portfolio.

He claims the success of its Three Ships whisky aligns “with the growing interest we’re seeing behind local brands. For many years international brands were perceived as being of a higher pedigree, though these views are changing. South Africans are coming into their own, and believe that they can compete with the best in the world in any field, be it art, fashion, sport or in our case whisky making.”

The same dynamic has benefitted the country’s pot still brandies, which have been “growing well, but off a tiny base”, says Reade‐Jahn. With a 3%‐5% market share, they can compete in terms of quality with the best from Cognac, but are outgunned in marketing spend. She mentions the emerging middle class in Johannesburg and Pretoria as being “very conscious of labels”, and says: “They’ll buy a bottle of Hennessy, not a shot, and put it on the table in a restaurant.”

Meanwhile “Diageo South Africa has really recovered to its 2018/19 level”, says its managing director, Gavin Pike: “Our volumes are a little bit behind, but revenues and margins are actually up quite strongly. Our portfolio strength is really across all main categories –the first is Scotch whisky, the second is vodka, then premium gin and rum.”

Although he accepts Scotch has lost share to international whiskies, be they Irish or homegrown ones, he claims “Johnnie Walker has been a key contributor” to the company’s recent growth. In Diageo’s latest half‐year results to December 2022, South African net sales were reported to have risen by 10%.

Polarised market

As well as shrinking somewhat, it seems the country’s Scotch market has become polarised. “There’s strength at the bottom, and strength at the top,” says Pike. “Our portfolio strength is in ‘premium’, and that’s meant we’ve been able to maintain a strong position in whisky.”

His colleague, Natalia Celani, marketing and innovation director at Diageo South Africa, adds: “We have registered phenomenal growth with Johnnie Walker Black Label, and we’ve just launched a campaign with the actor Jonathan Majors.”

In gin “our focus has been on ‘premium’, with Tanqueray and Tanqueray No Ten”, says Pike, but he accepts the category has plunged downmarket, with the ‘value’ segment accounting for a hefty 85% of volume in 2020, according to IWSR.

“There has been a real commoditisation happening in gin over the past two to three years, but innovations like Tanqueray Blackcurrant Royale have really helped keep consumers in the premium price points,” he says.

As for vodka, where Diageo’s locally distilled Smirnoff dominates, he claims: “We’ve really found opportunities around smaller formats, and these have played a critical role in consumer occasions and price points where the consumer, under pressure, is still shopping.” He mentions innovations like Smirnoff Infusions, which, at 23% ABV, “has really played to the desire for lower alcohol”.

It is early days for low‐and‐no brands in South Africa, but there has been plenty of activity. “We launched our first low‐alcohol spirit in the brandy portfolio, Viceroy Smooth Gold, in 2021, and are looking to launch a new low‐alcohol brandy for Klipdrift this year,” says Jekwa. Meanwhile, alcohol‐free Tanqueray 0.0 hit the market here in January, though “we don’t expect it become a huge brand any time soon”, says Celani.

And finally, there’s Tequila. It has a small presence in the market, which was badly hit by the on‐trade closures of 2020, and leans towards cheap, ‘mixto’ brands in South Africa. But Pike talks of “the emergence of a much more premium category, and a much more considered consumer who is observing the trends coming out of the US. We’ve seen phenomenal growth off a relatively small base, and we believe it will be a significant premium category in the future.”

If and when that happens, he will be ready, with a bottle of Don Julio in one hand, and a bottle of Casamigos in the other.