Scaling up: Japan’s new wave of whisky distilleries

By Tom Bruce-GardyneWith new distilleries multiplying at home, Japanese whisky is entering a more competitive and regulated era – one that will test its biggest names and its newcomers.

*This feature was originally published in the January 2026 issue of The Spirits Business magazine.

Last year one of the most popular Japanese whiskies celebrated its 40th anniversary. It was in 1985 that Nikka from the Barrel first appeared in its distinctive square bottle. To mark the occasion a new longer-matured expression called Nikka from the Barrel Extra Marriage was released in November.

“It has gone really well,” says Chris Seale, managing director of its UK importer, Speciality Brands. “Nikka is holding up a lot better than other products in the whisky category, and we’ve had a very good year.”

On its website, Nikka concedes that Nikka from the Barrel “does not meet all the criteria of ‘Japanese whisky’ defined by the Japan Spirits & Liqueur Makers Association [JSLMA]”. As well as malts from its Yoichi and Miyagikyo distilleries, it presumably contains some from its Scottish sister distillery of Ben Nevis, which Nikka’s owner, Asahi Holdings, acquired in 1989.

The JSLMA spent five years drafting the definition, which was essentially a copy and paste of the Scotch whisky regulations, to stipulate that the production and maturation for a minimum of three years in an oak cask all happens entirely in Japan. These guidelines were revealed in April 2021, with the association’s members given until April 2024 to comply.

It was initially reported as a victory for the category in its long-running battle with fake Japanese whisky. The issue was now dealt with, only it wasn’t, because as people soon pointed out, none of this applied to the dozens of producers who were not members of the JSLMA, and, besides, the definitions were just guidelines.

Clearly, something much more rigorous and all-encompassing was needed. Last March the association announced it would push for geographic indication (GI) status to give Japanese whisky the same protection as Bourbon or Champagne. At the same time, it unveiled a new logo that producers of the genuine article could display on their bottles.

For Nikka from the Barrel, whose owners have been more transparent than many, does any of this matter? “It does matter; categories deserve to be protected,” says Seale. “If it [the GI] were to happen, I think it’s good for the overall category, and the brand would have to adapt to that and make a decision on what’s best in terms of its production.”

Unless it went fully ‘Japanese’, it obviously won’t be able to display a logo, which its big rivals from Suntory have said they will. For now, Seale believes the category in the UK “holds a very unique position in people’s respect for whisky, and that’s one of the fundamental reasons why it’s able to command such high price points.

“There’s more and more competition right across the trade, from entry-level to super-premium. If you look at the total market, it’s under a bit of pressure, but that’s really at the cheaper end. At the upper end of the market the value growth is still there.”

Speciality Brands also imports Chichibu and focuses on its single-cask programme. “When we launched the London Edition 2025 at The Whisky Show in October, it sold out quicker than any of our previous editions,” Seale says of a whisky that retails for £250 (US$335).

Chichibu’s global brand ambassador, Yumi Yoshikawa, says: “The UK and Europe are among our strongest export markets.” Almost since Chichibu was founded, by Ichiro Akuto in 2008, the acclaimed boutique distillery has struggled to meet demand. Yet at present neither it nor the recently opened Chichibu II are operating at full capacity because “our focus is on establishing a successful start for our third distillery, the Tomakomai grain distillery”, says Yoshikawa.

Chichibu’s success has inspired many others. There are now more than 130 distilleries making whisky in Japan, including Kanosuke and Hatozaki, which was launched in 2017 as the whisky arm of Akashi Sake Brewery Co. “We’re a world whisky with Japanese inspiration,” says Rick Bennett-Baggs, Hatozaki’s global brand director. “By sourcing components globally but marrying and maturing them in Japan, we’re able to show that the best blends are greater than the sum of their parts.”

Bennett-Bags says the future Hatozaki Single Malt — distilled, matured and bottled entirely in Kaikyо̄ Distillery in Japan — will meet the full JSLMA requirements. “We are expecting to launch this in the next two to three years,” he says.

Kanosuke’s brand proposition is ‘next-generation Japanese whisky from Kagoshima’s Mellow Coast’. Its founder and CEO, Yoshitsugu Komasa, a fourth-generation shōchū producer, has incorporated some of shōchū’s production techniques into the whisky, while remaining fully compliant with the JSLMA definition.

“We do a long fermentation for over 120 hours, and use three pot stills with worm tubs,” he says of Kanosuke single malt. Maturation is in ex-shōchū casks, which are said to impart unique flavours of Japanese cinnamon, lemon and quince. The company also makes an Irish-style pot still whisky using malted and unmalted grain at its Hioki distillery.

Unfazed by competition

Backed by Diageo, following an investment through its now-defunct drinks incubator, Distill Ventures, Kanosuke saw its UK launch in September 2024. That moment awaits for Karuizawa Distillers (KDI), whose Komoro single malt will be released as a three-year-old this year. Its co-founder and master distiller, Ian Chang, appears unfazed by the number of distilleries it will be up against.

“The four major players in Japan are Suntory, Kirin, Asahi and Mars. For me, these are our main competitors,” he says. With its 500,000-litre capacity, Komoro is certainly bigger than most, and following a major investment by Seibu Holdings, it will be joined by Furaliss distillery, which is being built this year. When it comes on stream in 2028 it will give KDI a malt production of 2.5 million litres, propelling the company into the top three or four Japanese whisky makers.

“If Seibu, which is a huge group in Japan, with railways, hotels, and even a baseball team, hadn’t seen the potential in us they wouldn’t have invested,” he says. “It is a vote of confidence not just in KDI, but in the whole Japanese single malt whisky industry.” The company clearly has faith in Chang, who spent eight years as master distiller at Kavalan in Taiwan, which remains the biggest malt distillery in Asia on 9m litres.

The angels’ share KDI plans to produce steadily older malt whiskies at three, five and eight years, which won’t carry an age statement until it can establish a permanent, core, aged range similar to leading Scotch single malts.

“When I was at Kavalan, we couldn’t produce whisky with age statements because Taiwan is too hot, and you lose so much in evaporation,” he says. At Komoro, with two months of heat in summer and a winter that’s colder than Scotland, the angels’ share is 4%-4.5%.

If the Japanese whisky export boom stalled in 2023 it was thanks to China. The latest figures show its imports were worth ¥24.494m (US$157,178) in 2024, having slipped into second place below the US on ¥26.468m, followed by South Korea on ¥16.944m, and Taiwan on ¥15.943m.

The faltering Chinese economy has been compounded by politics, and Chang reckons relations between the two countries are at their lowest point since World War II.

IWSR reports that the category shrank by a compound annual growth rate of 3% in China between 2020 and 2024, and predicts it will continue to fall by 1% through to 2030.

In the US, tariffs of 15% are clearly unhelpful, but Chang believes American consumers “are quite willing to spend, so long as they have the quality”. For Fuji whisky, owned by Kirin Breweries, it’s early days. “We are still at a stage where we’re only entering the market,” says master blender Jota Tanaka. “We’re only in Texas, New York City and California, so we see more opportunities to make our brand grow.”

The company’s distillery, in the shadow of Mount Fuji, may have been around since 1933 but it only began exporting in 2017, launching the Fuji brand three years later. Since 2023, distribution in much of Europe has been handled by Pernod Ricard. “France and the UK are our key markets, but our key brand ambassador works for Pernod Ricard Poland, and he’s done a really good job in promoting our products there,” he says.

Tanaka adds: “We just want to create a beautiful, floral, fruity style that represents mother nature Mount Fuji.” Everything is done on site to make a single malt, a single grain and a ‘single blended’ whisky, the latter being a new subcategory, pioneered by Fuji. According to Tanaka, it’s the smoothness of Fuji that impresses first-time drinkers. He claims: “Some people say it’s like tasting a cashmere sweater.”

GI update

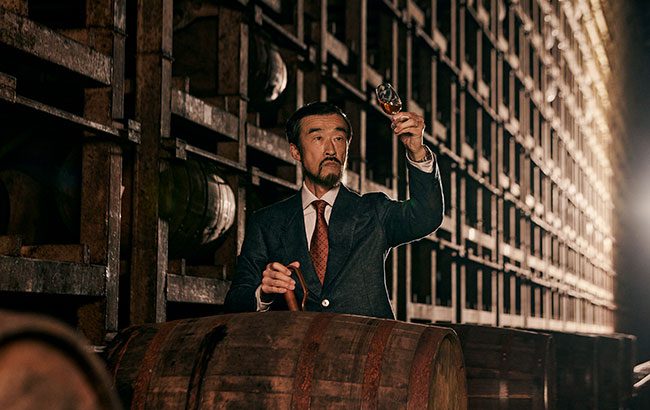

Fuji’s master blender Jota Tanaka (above) has been deeply involved in plans to give Japanese whisky GI status, which will apply to all countries in the World Trade Organization, and in launching a logo to go with it. The Japan Spirits & Liqueur Makers Association (JSLMA) is applying to copywrite the logo in key markets, while Japan’s National Tax Agency is to be approached to establish rules for Japanese whisky for all those who are not members of the JSLMA.

“We’re working on it, and within a year in could happen,” says Tanaka. In terms of the logo, he reckons that once the GI is established, “the majority of people will probably put it in the back label, but some might put it on the front.”

Quite who will certify the producers, whether they are part of the JSLMA or not, is unclear. Whatever happens, it seems Japanese distillers will continue to blend much of their production with imported bulk whisky.

The latter accounts for 60% of Scotch exports to Japan by volume, according to the Scotch Whisky Association.

Related news