The imitation game: where does the law draw the line?

They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but when it comes to brands emulating others, where does the line between ‘inspired by’ and ‘copied’ fall, and how can brands protect themselves from copycats?

In February 2023, British retailer Marks & Spencer (M&S) won a trademark lawsuit against discount supermarket Aldi over a gin liqueur range containing gold flakes that was released in November 2021.

The lawsuit, which was filed in December 2021, alleged the German retailer’s Infusionist Gold Flake Gin Liqueur range infringed on the trademark of M&S’s Light Up Snow Globe Gin Liqueur, which it released in autumn 2020 ahead of the festive period.

An M&S spokesperson said at the time that the judgement demonstrated the importance of protecting its innovation: “Like many other UK businesses, large and small, we know the true value and cost of innovation and the enormous time, passion, creativity, energy and attention to detail that goes into designing, developing and bringing a product to market.”

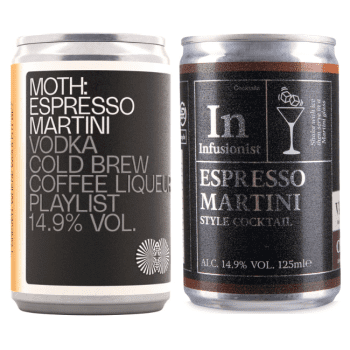

However, anyone who takes a quick scan of Aldi’s own-brand spirits aisle today will note that this case didn’t put Aldi off, and many may feel a sense of déjà vu when perusing its shelves, especially if they’re familiar with vodka brands such as Au, Smirnoff, and Grey Goose, as well as both Gordon’s and Caorunn gins, or pre-mixed brands Funkin or Moth. Each of these brands – a mix of conglomerate-owned and independent – harbours a recognisable resemblance to the supermarket’s own-brand products, in both appearance and flavour profile.

Brands but cheaper

But this is the supermarket’s modus operandi. Rowena Tolley, brand protection partner at intellectual property firm Kilburn & Strode LLP, explains that Aldi’s self-professed business model is built around ‘Like brands, only cheaper’.” However, she says: “There is a very fine line between being ‘inspired by’ and blatant copying. Sometimes they get it right, sometimes they cross the line. And it’s often hard to know where that line is until it goes to court.” That is if it goes to Court at all.

To the untrained eye, many consumers may find themselves asking, ‘how do they get away with it?’ And is there anything a brand can do to protect itself from this style of imitation?

Nicholas Pfeifer, partner at Smith & Hopen in Tampa, Florida, explains: “Generally speaking, there are different types of intellectual property to protect against this type of copying. Trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets, and even design patents can be used depending on the circumstances. Each has its own benefits and limitations.” Trademarks, he says, can protect a brand’s name and logos, potentially even the bottle design and colour scheme if there is enough consumer recognition, while copyrights can protect the logo and label; trade secrets can protect a brand’s recipe; and design patents – called ‘registered designs’ in the UK and EU – can protect the design of the bottle.

Trademark and design attorney John Noesen says the line between what is inspiration and what is a copy is the core question in most of the cases his Belgium-based firm Winger is involved in. “The case law gives us some tools to evaluate this, but ultimately it is up to the ‘subjective’ appreciation of the judge,” he says.

Noesen clarifies that blatant copying behaviour can be considered “unfair competition” in both the US and Europe, which is a ground often used against copycats.

However, in the UK, this law does not exist, Tolley says. “Our UK equivalent for protecting unregistered IP rights like this is ‘passing off’, which protects the goodwill of a business, often closely associated with the get-up of a product. The problem is that to succeed in passing off, you need to prove there has been some confusion,” she says, noting that, in the case of Aldi, consumers would need to have mistakenly bought the Aldi product thinking it’s the real brand owner’s. “But in most cases, consumers aren’t confused – they are very aware that this is not the real thing but an imitation, especially since the copycat will often use a very (or at least sufficiently) different name, knowing that consumers typically refer to products by name and it’s just the wider get-up they copy. So any action based on passing off often fails.”

As long as confusion hasn’t arisen, one might ask where the harm is in companies using existing brands as a starting block for their own ‘innovations’. However, there are of course other factors at play, as seen in the case of Diageo vs Deutsch Family Wine & Spirits, which concluded in Diageo’s favour in 2022, when Deutsch was forced to stop the sale of its Redemption whiskey after it was found to dilute the Bulleit trademark.

Diageo initially sued Deutsch Family Wine & Spirits in 2017 over the redesign of Redemption whiskey, claiming the bottle had been ‘revised to closely mimic’ its Bourbon and rye whiskey brand, Bulleit.

While the judge sided with Diageo, and banned the advertising, promotion and sale of Redemption whiskey in its current flask-shaped packaging, the ruling concluded that the packaging did not infringe on the Bulleit trademark by creating consumer confusion, and the jury also rejected Diageo’s allegation that Deutsch acted in bad faith when designing its Redemption bottle. As such, Diageo was not awarded the US$21 million in damages the company had sought.

Early protection

To avoid the legal hassle that comes with another brand benefitting from a design or concept, Tolley says seeking early protection for a brand’s intellectual property (IP) is key.

“If you can’t stop [other companies or brands] through passing off, many brand owners look to rely instead on registered IP protection – typically trademarks or registered designs. Companies should consider filing trademarks not just for the name or logo, but wherever possible in the get-up of a product. Designs also afford great protection, but can only be filed in the first 12 months after the product/its get-up has been made public. Many food and drink manufacturers simply don’t think about this early enough and miss the boat to file, or they don’t realise how successful the product is going to be and then by the time they realise, it’s past the 12-month point and it’s too late.

“If you act early enough, though, registered designs can be a really useful tool – and can cover all kinds of get-up label layouts, bottle shapes, packaging shapes, fonts, and patterns. They are very underrated and, in my view, underused.”

Noesen also advises that this kind of design protection gives the clearest defence to a brand. However, he warns that “designs need to be ‘new’ when filed; this means that they cannot be made public before the filing. Even your own publication on your website or social media can be detrimental to the validity of your own design.”

Alan Rae, owner of copyright consultancy © Here (See, Here), adds that while a brand can do a lot to protect itself, “sadly, many don’t because there is still a worrying ignorance, especially among small and medium enterprises in the industry, about IP”.

Rae continues: “Companies only tend to become interested in IP if they are accused of infringement or discover that another company is copying their products, which have probably had considerable investment to bring them to market.”

Conversely, he notes that when it comes to copyright, brands do have an “automatic right”, however this can only be registered in the US and a few other countries, but not in the UK. Nevertheless, he says just because it isn’t registrable in the UK doesn’t make it any less significant. “If creators have a paper or digital trail, they should, at every opportunity, use the copyright symbol (©) on their work along with copyright warnings, such as those you see in the frontispiece of books and at the end of movies and TV programmes,” Rae says.

However, he warns that ideas alone do not have copyright – they must be written down, recorded, photographed, sketched out, or coded: “In other words, they have to be ‘fixed’ for copyright to exist.”

It should perhaps go without saying that the ‘fixed’ content has to be original, but this is where a secondary issue comes into play – how to prove originality. “It’s very difficult because all creators are likely to have been influenced or inspired either consciously or subconsciously at some time. The creators may also just blatantly copy in the hope that they are not caught,” Rae adds.

Tolley also notes that “the assignment of copyright in works created by branding and other creative/design agencies (such as packaging, logo and get-up, for example) is often overlooked, so the brand owner doesn’t always own the rights it thinks it should. Checking the ownership of these assets is another way that brand owners can put themselves in the best possible position to take action should that become necessary.”

Options for consumers

The issue for many brands that have found themselves the inspiration for another brand’s product is that someone else is benefitting from their hard work, and, in most cases, financial investment.

At the beginning of this year, cider brand Thatchers lost its High Court trademark battle with Aldi after it accused the retailer of copying its cloudy lemon cider. Thatchers argued that it had spent close to £3 million (US$3.81m) on marketing, only for Aldi to go on to achieve “extraordinarily high” sales of its Taurus Cloudy Lemon Cider product after a “lack both of development investment, or marketing spend”.

This could “only have been achieved by reason of Thatchers’ investment in the Thatchers product”, the Somerset-based family producer had argued. While this may be true, a judge ruled that there was a “low degree of similarity” between the rival products and, more importantly, “no likelihood of confusion” for consumers.

However, some brands may find themselves reluctant to challenge copycats, or, as Tolley notes, might choose to play these disputes out over social media instead, with each party seeking to win the PR battle, irrespective of the legal battle. That can work particularly well when the copied party doesn’t have the funds or inclination to go to court (or when it thinks it’s more likely to win over the public than a judge), as seen earlier this year when Lind & Lime Gin co-founder Ian Stirling took to Instagram to call out the design of a new Tequila from BrewDog.

Speaking to The Spirits Business in February, Stirling said: “I know we are all inspired to some extent by other brands, but this crosses that line with two middle fingers waving merrily in the air. They knew we’d notice, but simply don’t care because they’re a massive company and we’re not.

“You don’t catch them producing a bottle that looks like a Coca-Cola bottle. It feels as though there is a power dynamic at play. All we can do as a small producer is call it out when we see it and shout as loud as we can.”

Meanwhile, there are some brands that have been invited into the fold of retailers such as Aldi, and have subsequently chosen to approve the ‘copied’ product, as Pfeifer explains: “When it comes to big stores like Aldi, there is often an agreement in place with the brand owner. That agreement allows the brand owner to sell its goods in the store so long as the brand owner agrees that the store can copy the appearance of the brand to some extent to sell a store-branded version of the same product. In such instances, the contract typically governs rather than the intellectual property rights.”

While this wasn’t the case for ready-to-drink (RTD) canned cocktail brand Moth, which found itself the inspiration for one of Aldi’s most recent product launches, co-founder Rob Wallis has chosen to take the imitation as a compliment, and sees it as a positive step forward for his brand’s category.

“There are an increasing number of players, both branded and own-label in RTD, which is a positive sign of the momentum the category is experiencing. Moth’s success has been built on an unrelenting commitment to delivering high-quality products. We are confident that with our continued focus on this we will be able to stand out from the competition by offering cocktails that are genuinely bar-quality cocktails with all the convenience of a can of beer.

“However, it’s great that there are a variety of RTD options for consumers regardless of where they shop and their budget, and ultimately, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.”

So to the question, ‘how do they get away with it?’, the answer is multifaceted but ultimately pretty simple. When it comes to using other brands as benchmarks for its own products, Aldi ensures that there is no risk of consumer confusion, and that copyright guidelines are adhered to and trademarks and registered designs are not (regularly) breached. In short: Aldi is doing nothing wrong, and the consumer is ultimately the one that wins as a result.

The Spirits Business reached out to Aldi for comments, but did not receive a response.

Related news