SB visits… eight pisco bodegas in Peru

Pisco is still a rather unknown quantity to many in the western world and to properly inform one’s self on Peru’s national spirit, the obvious move would be to just fly out to South America…

So, on that thought, The Spirits Business took the 19-hour journey (via Brazil) to Peru on the invitation of tourism board Promperu to gain an on-the-ground understanding of the spirit.

Pisco may be distilled from wine grapes but don’t call it a type of brandy – ask anyone in Peru and it’s very much its own beast. There is no sugar, no additives, no water and no wood, and it’s colourless and clear. It is 100% a product of the grape, which means there are no shortcuts when it comes to making it, and Peru’s weather conditions play a massive part in the final outcome.

It can be made from eight grape varieties, divided between non-aromatic grapes said to come from Spanish settlers (Quebranta, Uvina, Mollar and Negra Criolla) and aromatic grapes (Italia, Torontel, Moscatel and Albilla). Last year, SB also looked at how the category is widening its scope, and how producers have confidence in its ability to grow.

On our visit, we managed to squeeze in eight distilleries across four days, and cover the five coastal valley regions where pisco is produced: Lima, Ica, Arequipa, Moquegua and Tacna.

If someone has the idea of starting their own Peruvian pisco brand, then they have to do it here, as only these regions are recognised by the denomination of origin (DO) in Peru.

By the end of the trip, much pisco had been consumed – all in the spirit of education, of course – and now, back in London, fully recovered, we’re ready to report back.

Behind the scenes

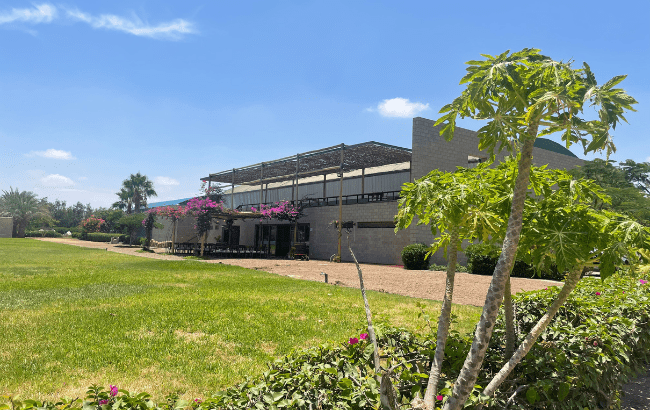

It felt only right to visit pisco first, so off we went to Bodega San Nicolas, nearly 250km south of Lima, which produces 1615 Pisco.

Dubbed a ‘boutique distillery’ due to its small size (30 hectares), it is named after the year in which grapes first arrived in the region from Europe.

We were given a walkthrough of the vineyard from where the grapes are cultivated (we were informed this geographic area is particularly kind for Quebranta), though there were no grapes on sight as the harvest had finished 15 days before our arrival.

Traditionally the harvest ends in March, but it came a little earlier this year due to the 30-degree heat. This, sadly, meant a smaller yield for the producer.

A behind-the-scenes tour of the machinery and an explanation of the fermentation process followed, before we sat down for our first tasting session, and for a few cocktails; a Pisco Sour and a Chilcano, Peru’s two most popular serves (don’t ask us to pick a favourite, though). While we would have happily sat here and continued to drink cocktails all day in the sun, duty called and we were soon on the move again.

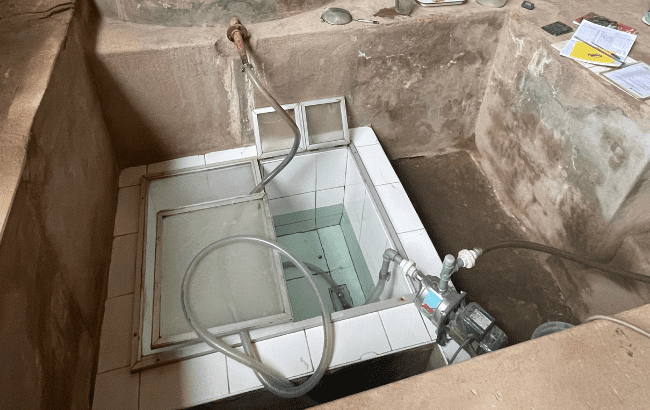

Stopping by Paracas Bay for lunch (we ordered ceviche, naturally) we next headed to Ica, to La Blanco, the oldest pisco producer in the region where they still do it the traditional way – via a falca, a tank built from copper at the bottom with the rest made from limestone.

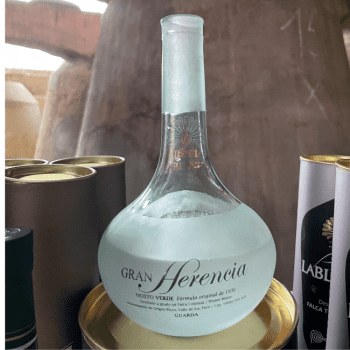

The space still noticeably carries damage from the 2004 earthquake and is very old-school in its look (read: ancient). They make two Mosto Verde piscos here, which is a premium style; there’s the classic produced after six days of fermentation, and their own version, the Gran Herencia, made after two days of fermentation, which you can see pictured.

Twenty kilos of grapes are needed to produce just one bottle of this one. For the regular Italia pisco, it is 7kg per litre. After the tasting, we climbed up the tanks to observe the pisco resting and also had a look at the final part of the distillation process – where we sipped it straight from the source.

We were up bright and early the next morning to catch a flight from Lima to Tacna for the second leg of the trip. The grapes in Tacna are reputed to be sweeter and stronger, producing pisco with more body and aromas.

After quickly dropping our gear off at the hotel, we were whisked off in the team van to distillery number three, Bodega de Vinos Spirit y Piscos Miculla.

It’s a family-run distillery founded in 2009 and owned by Giovanni Sánchez Ayala, a professional bartender, enologist and taster. The distillery makes pisco, red wine and liqueurs, which Ayala proudly tells us can be found on the shelves of some of Lima’s best bars, like Carnaval.

Warm welcomes

After the introductions, a lady dressed in traditional wear placed herself into a bucket full of Negra Criolla (black grapes) and began treading – and dancing – on its contents, until crushed. This was explained as a traditional maceration technique used centuries ago, and as entertaining as it was to watch, Ayala assures us that they now make use of the latest technology to produce their pisco.

We were then taken outside and treated to more traditional dancing (called ‘pisa de uvas’), though not just for our entertainment, or for show, but to ward off bad spirits. If the dance wasn’t performed, then the grapes would turn out bad. Call it superstitious, but they don’t take any chances out here.

Post-dancing and a prayer to Pachamama later (called an anyi, or a ceremony for the Incan goddess for a good vendimia, or harvest of the grapes), we were led around the distillery, past the resident flock of sheep, and to a dozen Andean cloth-covered tables for a tasting, which included the family’s Licor de Damasco, an apricot liqueur made from the stone-fruit grown in Tacna.

We were then tasked with making our own Peruvian cocktails using a variety of the family’s spirits where we can confirm the results were ‘excellent’ and that our mixology skills were ‘very impressive’. At least, that’s what our hosts told us.

Having downed our excellent cocktails, we were off once again to the second distillery of the day, Sobraya. This family-owned distillery was founded in 1991 and takes its name after the vines in the area.

The grapes here, black criolla, were 24 days away from harvesting when we came and the season’s soaring temperatures had proved an issue so the family had to use ice to cool the grapes down.

We stepped inside, among the barrels, and were given a rundown of their piscos before dutifully getting to try them all.

New day, new destination, new distilleries. Day three of our pisco tour saw us head further south down to Moquegua, and more specifically the historic Biondi winery – which has been running since 1972.

As its name suggests Biondi winery produces wine but its pisco has even footing and we mooched around the tanks and observed as the distillery’s quality control chief (pictured) explained his methods to us. They were currently processing Quebranta grapes – the most popular variety in Peru – which needed six to eight days for fermentation.

Tours and tastings

The grapes arrive here by truck at 5am and 5pm every day, and we managed to sneak a glance at the unloading process. The chief stressed the importance of controlling the temperature in the fermentation tanks – with 25 degrees Celsius being the maximum temperature and 18 degrees the minimum.

Having ingrained all the information firmly into our minds, we then dived into the mandatory tasting session which culminated in a few Pisco Sours made in the bar that Biondi handily has on site.

Following a lunch in Moquegua, which, yes, included guinea pig (a delicacy in Peru), we made our way to our next stop, which was El Mocho. Through the big gates, we were greeted this time by none other than an alpaca, which was a novelty, as well as many dogs, birds and a few bulls out the back. The place doubles as a petting zoo, unofficially.

The evening started with the house tour from José Antonio Salas, who runs the winery having followed in the footsteps of his father, Don Tomas, who has an altar dedicated to his memory in the centre of the space. Due to the high altitude the production here is harder, but in any event, Salas makes three types of pisco and wine – both Burgundy and Italia.

José was adamant that we tried all his piscos and who were we to say no to his warm hospitality? So, we ended up staying until nightfall, more than a few hours over schedule…

The next day, we faced a four-and-half-hour journey to get to Arequipa from Moquegua, but the landscapes en-route were spectacular – passing through the mountains and desert – and naturally, we also stopped at two distilleries along the way, our last of the trip.

The first was Torres de la Gala, positioned in the La Joya valley, about an hour out from Arequipa. Octavio de la Gala started the winery with his wife 25 years ago and told us his goal was to give a true representation of Peruvian pisco. The altitude here is 1,600 metres above sea level and it feels like everyday is a sunny one (lucky them).

Although the arid desert valley setting – comparable to Mars – may not seem like it at first sight, the land is very fertile (the white colour from the hills is brought upon from minerals) and alongside wine and pisco, they grow their own vegetables and avocados, which make for a heck of a pisco pairing snack, combined with crackers.

Don Octavio and his son Martin, who helps his father run the winery, gave us an in-depth overview of their proud history, showing us photos from the past and sharing stories. After tasting their pisco and snapping a few group photos, we moved on our merry way and towards Socabon – the last distillery on our tour.

Latin America’s oldest bodega

Socabon is recognised as one of the ancient distilleries and is said to have started making wine way back in 1557 where it got its grapes from Spain, when many came to the Vitor Valley – where Socabon is situated – and settled in the area. We were told by our guide that it is in fact the oldest bodega in Latin America.

As we arrived, we had our most left-field welcome yet: from two puppies, who proceeded to disarm us with their cuteness. Having finally been pried away from the puppies, Miguel Angel Cornejo, the vineyard’s owner, then took us inside where we observed wine containers that date back to the 1700s – the space had an air of museum to it.

As for pisco making, Socabon keeps some old traditions (the stills are covered in clay), but the distillation process is performed in copper.

And though there were many strong candidates on the trip, Socabon may have won the competition for most aesthetically-pleasing tasting room – just look at the picture to the right.

If you think by this point we’d be totally pisco-ed out, think again. After Socabon, we arrived in Arequipa for the last leg of the trip, and while it didn’t involve any distillery visits, it did feature even more pisco.

Related news

Cocktail stories: Speed Bump, Byrdi