Popularity contest: how pisco is looking to grow

Pisco is often considered to be an underdog in the spirits world. But by widening its scope and sampling opportunities, producers are confident its popularity will grow.

*This feature was originally published in the March 2023 edition of The Spirits Business magazine.

The strength of the pisco category comes not only from its diversity – from its two countries of origin, Chile and Peru, and the variety of styles available – but from the loyalty of its domestic markets too, not to mention the popularity of the Pisco Sour.

But export is a priority for many producers too, as is the promotion of different serves and new consumption occasions.

The overall category has faced, and continues to face, its share of challenges, not least the pandemic, although there are already signs of recovery from that. According to IWSR Drinks Market Analysis, global pisco volumes grew by 8% in 2021, compared with 2020, with value increasing by 9%. IWSR forecasts don’t see that level of growth necessarily continuing, however, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) drop of 0.5% from 2021 to 2026.

“The pandemic was very tough on the pisco industry,” says Jaime Escobar, brand manager of Chilean pisco co‐operative Capel, who describes an overall decline in 2020 primarily driven by the on‐trade, followed by a return to 2019 figures in 2021, led mainly by the offtrade. Growth in 2022, meanwhile, was boosted by the on‐trade, he says, “but that channel is still less important now, relative to the others”.

The on‐trade has traditionally been an important one for the pisco category, for a number of reasons. Among these, as Jose Luis Hermoso, research director at IWSR, explains, is related to the Pisco Sour. “The fact that pisco’s prominent and most revered cocktail is difficult to reproduce at home, as it involves egg whites, has been a blocker to the category’s development, and recent on‐premise closures during the pandemic have had an impact as well,” he says.

The on‐trade continues to be a priority for the category, says Ricardo Romero, director of the London office of Promperu, Peru’s trade commission.

He believes that in the UK “consumption still has ample room for growth, and is currently focused primarily on the on‐trade, as many speciality cocktail bars have included pisco‐based drinks on their menus”.

Chris Seale is managing director of Speciality Brands, which includes Peruvian pisco Barsol in its portfolio. “The on‐trade remains the key growth channel, with the iconic Pisco Sour the main consumption driver for the category,” he confirms. But he adds that sales of the brand have shifted towards retail in the UK in recent years, driven by e‐commerce, with the on‐trade’s share declining from 95% to 80%.

“The increase of Peruvian outlets in the UK such as Coya and Pachamama has had a positive impact on driving awareness and consumer understanding of the category,” continues Seale. “Outlets that celebrate South American cuisine, culture and drinks, such as Amazonico, will certainly help with spearheading the development and popularity of the Pisco Sour, but we still need more bars and restaurants to put pisco on their menus.”

Versatile liquid

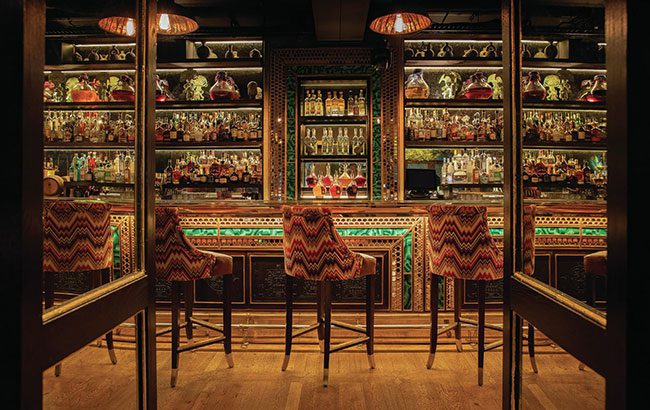

Sany Bacsi, corporate bar manager of Peruvian restaurant group Coya, is seeing this happen already. “Bartenders around the world are discovering newer depths of this product, and are exploring interesting new ways to build cocktails around it,” he says. At Coya, there is a dedicated pisco category in the cocktail list, showcasing different styles and grape varieties, as well as a Pisco Library featuring in‐house infusions. “Pisco is an amazingly versatile liquid, with interesting complexity and a lot of soul,” adds Bacsi.

At pisco bar Oroya, in The Madrid Edition hotel in Spain’s capital city, consumers can explore the 20‐strong selection of Peruvian piscos via tasting flights. “The Pisco Sour is still a major hit, but bartenders have learned that pisco is really versatile,” says head bartender Matteo Bernardo.

The Punch Room, a bar also in The Madrid Edition, offers yet another way for consumers to appreciate the category. “We’re able to serve different styles of Punches featuring pisco, which gives our guests another perspective on the category, and its possibilities in mixed drinks,” says head bartender Simone Ruta.

Peru’s ambassador to the UK, Juan Carlos Gamarra, believes that this move beyond the category’s main, iconic cocktail is an important one. “There is a need to continue to educate mixologists, bartenders and consumers about the different cocktails and ways to drink pisco beyond the Pisco Sour,” he says.

The category faces broader challenges, Gamarra adds. “Pisco has not been able to penetrate the mainstream market, given the difficulties and levels of investment required to enter big retailers and chains,” he says. “Since companies are relatively small, and the industry is fragmented, it is difficult to compete with the big budgets of other spirit categories at the moment.”

IWSR’s Hermoso says: “Outside of Chile and Peru, where pisco is the leading local spirit, the category is still relatively niche. There have been several brands that have tried to enter the US market in the past and make pisco more mainstream, but with mixed results.”

For Capel’s finance manager, Juan Pablo Riquelme, the challenges faced by the category are multifaceted. He describes “a complex national and international scenario, with high inflation, dollar prices and high costs transferred to the distribution chain”. Over the past two years, “the pandemic scenario and economic instability in the country has led to us being more perceptive in growth strategies, and more creative”.

Escobar agrees, saying that the category’s development, specifically in the on‐trade in Chile, “is challenged by the economic reality of the country, with the consumer price index increasing by around 1% monthly”.

Cristobal Cofré Torres, global brand ambassador of Pisco El Gobernador, says: “The challenge is to expand the number of countries that import Chilean pisco.” But he adds that this is already happening, at least to some extent. “In the national market we are seeing new brands every week, with amazing quality, and in the international market we are growing a lot, with many brands opening new markets, and [trade association] Pisco Chile striving for the category to grow,” he says.

Meanwhile, climate change is having a serious impact on the category, according to Juan Carlos Ortúzar, CEO of Chilean brand Pisco Waqar. “The main challenge facing the pisco industry is global warming, which has caused the production of grapes to decrease, and an increase in price,” he says. “In addition, the challenges posed by much more demanding consumers must be considered, in regards to the traceability of each product, environmental care in the production of pisco, and health issues that have become very important after the pandemic.”

Premium piscos

Those same consumers are demanding more premium piscos. “Despite the global economic situation, consumers in the domestic market continue to seek an attractive price‐quality ratio, so continue to seek premium products,” says Ortúzar.

The same is true for pisco’s export markets, according to the IWSR’s Hermoso. “Premium brands are likely to do best, given consumer interest in higher‐quality spirits,” he says.

Producers are rising to the challenge, not only creating more premium expressions, but making use of the category’s versatility to innovate too. This range of styles allows the category to “offer different experiences to consumers, such as the Piscola [pisco and cola], the popular cocktail in Chile”, says Hermoso. “Lately, some pisco brands have been launched to compete with añejo Tequilas or aged whiskies for the sipping occasion,” he adds.

Among these new aged variants is the latest from El Gobernador. While the original is aged for a year in stainless steel vats before being bottled, the new variant, El Gobernador 35, is aged in ex‐pisco barrels for two to three months, and uses a slightly higher proportion of Alexandria Muscat grapes to highlight its fruit aromas, according to Torres.

“The category is showing a lot of innovation, with many new piscos and new varieties being launched,” confirms Ortúzar, pointing out the success of the latest addition from Waqar in Chile. The distiller has created what it claims is the first of its kind; a smoked grape pisco called Black Heron.

Launches like these further broaden a category that’s already noteworthy for its range of styles, and subsequent versatility. As Gamarra puts it: “The versatility of pisco is endless, and this is a message we are looking to position in the consumer’s mind.”

For Promperu’s Romero, the way to reach those consumers is via the on‐trade. “Peru’s promotional strategy of the national drink in the UK has been driven primarily by activities with bartenders and mixologists, providing the necessary knowledge and tools in the trade for successful recommendation and sale to the end consumer.”

Seale, meanwhile, believes that the untapped potential of the category lies in its range of grape varieties. “Pisco is still a niche category, very much focused on the Quebranta variant. One of the biggest challenges will be driving awareness of other varieties, such as Torontel and Italia, which tend to drive a price premium,” he says. “With an offering as broad as the wine category, only education will encourage consumers and the trade to trade up and further explore pisco.”

The trick for the category, it seems, for the Peruvians and Chileans alike, is to make the most of that breadth of style and versatility, and continue to spread the word far and wide.

Related news

Two Stacks: relevance essential for driving growth