Rockies road: how Canada’s spirits market is evolving

The retail landscape in Canada is changing and brands are keen to appeal to an influx of immigrants to the country. But they must factor in the economy, and consumers’ higher expectations.

*This feature was originally published in the August 2023 issue of The Spirits Business magazine.

This year Canada announced that its population had hit a record 40 million, double what it was in 1966. Last year alone it grew by a million, and 96% of that was down to immigration, led by Indians on 118,000, followed by Chinese on 32,000. “It’s got the fastest growth of any G7 country,” says Nicolas Krantz, president and CEO of Pernod Canada.

He believes the influx of new consumers makes the spirits market far more dynamic than it would be, and is one of the things that sets Canada apart from the US. With Scotch whisky, for example, he says: “On the one hand it’s a mature market, but it’s also very open to innovation.” The fact there is a strong Asian population, particularly in western Canada, has only benefitted a brand like Chivas Regal, which has long been popular in Asia.

Another key difference from its neighbour to the south is the presence of liquor control boards, led by the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), where annual spirits sales are running at 7.6 million cases on a par with the previous 12 months, according to trade body Spirits Canada. That is more than double the next two biggest provinces combined, with Quebec on 3.5m and British Columbia on 3.4m, followed by Alberta on 2.9m. In broad terms, eastern Canada is about control boards, the west is split roughly 50:50 between control and independents, “while in the middle, Alberta is principally private retail – so, much closer to what you have in the US”, explains Krantz. “Many people say that liquor boards are difficult to work with, but when you have a customer like that you are a key partner, and you move fast. The level of distribution we have is huge, with every brand higher than 85%.”

Having worked in Europe supplying giant retailers like Tesco, Carrefour, and Lidl, he believes you can have a closer relationship with the LCBO in Canada. “They’re there to raise revenue for the government, but I’d probably say there’s a greater spirit of partnership and support. Their mandate is to bring the world to Canadian consumers, and with wine, for example, you have far more choice than you do in Europe.”

These varied routes to market mean “you cannot have a one-size-fits-all [situation]”, he says, but with the liquor boards, “when we launch an innovation, we can see straight away how it has performed, so it is a nice territory [in which] to test and learn.”

Jeff Branson, Bacardi’s vice-president and general manager for Canada, agrees. “The LCBO, with its 600-plus stores in Ontario, allows you to launch very quickly, and it is a market that is very rich in data,” he says. But in terms of marketing, where Bacardi’s focus is above the line, he believes it makes no difference where you are selling in Canada.

Trend for deregulation

The only province to go the Alberta route recently is Saskatchewan, which sold off the last of its public liquor store permits this year, for around CA$45m (US$34m). Krantz says: “I see more of a trend for deregulation. In Ontario in any grocery store you can now find beer and wine, but not spirits.” That anomaly is down to an old, anti-hard liquor mindset, in his view – something Spirits Canada is keen to change. Its message to the powers that be is: ‘How come you can have wine from Australia, but not a whisky made in Ontario?’

The country’s overall spirits market has gone flat since its 30% surge in 2020, followed by 10%-11% growth in 2021/2022, according to Patrick Sweeney, Beam Suntory’s managing director of Canada and Canadian brands. “As of the latest three months, it’s 0.5%, so we’ve definitely seen a slowdown,” he says. Within that, “single malts are -6% and Cognac is -16%, but on the positive side we’re seeing some really great growth in Japanese whisky, of 24%, and in premium Tequila and Irish whiskey”.

While Canada is the third-biggest consumer of Tequila after Mexico and the US, Sweeney concedes that margins are definitely an issue, thanks to the country’s high taxation and the cost of the raw ingredients. “Three or four years ago in Canada it was all about gin, now it’s about Tequila, which has become the number-two category in on-premise,” he says. “But it’s widely known that profitability is a challenge for everybody in Tequila. Hopefully, agave prices will not stay where they are forever.”

According to Krantz, you can expect to pay 20%-25% more for a bottle in an LCBO store than you would typically pay for the same brand in the US.

There is no issue with demand. “I’d not lived in Canada since 2008/9 when Tequila was in its infancy,” says Branson. “Now I’ve moved back, in the past year I’ve seen an explosion in the category. People are discovering the craft of brands like Patrón, and consumers are astutely aware of just how good the quality of Tequila can be.” He claims that Patrón, priced at a distinctly super-premium CA$85 a bottle, grew by 10% last year in Canada, and is up by 123% since 2018.

In brown spirits, “Canadian whisky is still huge”, says Krantz, whose main brand at Pernod is JP Wiser. “Consumers still see it as a great place to go, and it’s also a very versatile category for cocktails, and the price point is very competitive.” He would love producers to talk more about provenance than price. In his view Canadians tend to perceive Bourbon, Irish or Scotch as “a bit more of a premium occasion”.

Beam Suntory’s Sweeney says the category is “big business for us with Canadian Club and Alberta Premium”. The company is planning to launch its Invitation series for Canadian Club, or CC, this autumn. At present there is a focus on RTDs, with Canada apparently the world’s fourth-biggest consumer of ready-to-drink. “We’ve hero-ed CC and ginger ale, and that has helped us recruit younger people,” he adds. Pernod Ricard has launched a JP Wiser 10-year-old that “has been extremely successful in year one”, says Krantz.

In terms of other whiskey, “Jameson is still a powerhouse”, says Sweeney about one of Pernod’s top-performing brands. “When you walk into that 3ft-4ft Irish whiskey section in a Canadian store, it’s 80% Jameson – they really own that space. But where you’re really seeing growth in Irish is in that premium, super-premium subset, so the likes of Writers’ Tears, Green Spot, Redbreast, and Jameson Black Barrel.”

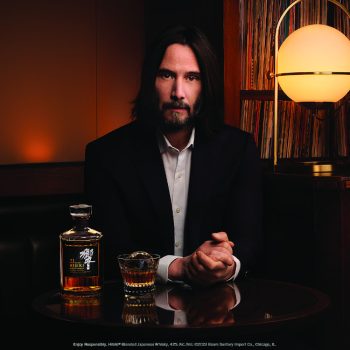

At Beam Suntory with its stable of Japanese whiskies, the main focus in Canada is on Toki, which is growing by 35%, apparently. “We do get a little bit of Hibiki and Yamazaki,” he says. This year the company is celebrating the 100th anniversary of Suntory with a short film made by American director Sofia Coppola, starring Canadian icon Keanu Reeves.

At Beam Suntory with its stable of Japanese whiskies, the main focus in Canada is on Toki, which is growing by 35%, apparently. “We do get a little bit of Hibiki and Yamazaki,” he says. This year the company is celebrating the 100th anniversary of Suntory with a short film made by American director Sofia Coppola, starring Canadian icon Keanu Reeves.

“Bourbon has started to expand in Canada,” says Jeff Branson. “And last year we launched Angel’s Envy, which retails for around US$80, and is now the country’s number-one super-premium Bourbon, twice the size of its nearest competitor.” But with rum, where Bacardi is clearly the lead brand, he describes the market as “stable,” and admits that “rum hasn’t been able to enjoy the success of other categories like super-premium vodka, whisky and Tequila”. For now, it’s hard to imagine releasing a rum at anything like the level of Bacardi’s recently launched Patrón El Cielo Tequila, which currently sells for CA$249.99 in British Columbia’s liquor stores.

Consumer confidence

In the background are economic headwinds affecting people’s purchasing power. This time last year, the country’s rate of inflation peaked at 8.1%, but it has come down significantly since then, to just 2.8%, as of late July, according to Patrick Sweeney, who says: “Consumer confidence is the biggest thing at play right now. Gas prices have come down and so has telecoms, but with interest rates of 5%, mortgages are on people’s minds, groceries are still very expensive, and rentals are at an all-time high.”

The mantra of premiumisation, of people drinking less but better, is as strong in Canada as anywhere. “Consumers are seeking affordable luxuries, and Covid and cocktail culture prepared them to expect more,” says Branson. “At-home consumption taught them to drink better-quality products.” Yet with their own inflationary pressure to deal with on cost of goods, he accepts that brand owners such as Bacardi have struggled to pass them on in increased prices. “We absorb the majority of them,” he says, while Sweeney admits to “some margin erosion”.

Another point of difference that sets Canada apart – is cannabis, legal since 2018. Five years on, it seems spirits have seen little or no impact. “The data we have is that it has taken share from beer, but that cannabis-based drinks are a very small part of it,” says Krantz. “And I see a massive difference. Cannabis is a commodity. There’s no loyalty and no brand building.”

Related news

Top cocktail recipes for March 2026