Liqueurs get a boost from at-home cocktails

Thanks to the revolution in making cocktails at home, liqueurs – once almost the outcasts of the drinks world – are enjoying a huge resurgence of interest.

*This feature was originally published in the November 2021 issue of The Spirits Business magazine.

Dutch drinks group De Kuyper claims to have survived at least 10 pandemics since it was founded in 1695. It got into liqueurs during Prohibition in the US, and, having acquired famous heritage brands such as Mandarine Napoléon in 2009 and Cherry Heering in 2017, is now said to be the world’s largest producer of cocktail liqueurs. This clearly matters to a firm with the bold stated ambition ‘to own the cocktail’.

“With the first lockdown we definitely saw a shift as people started to make cocktails at home,” says Albert de Heer, De Kuyper’s global marketing director. “People overcame the barrier of doing it themselves with the ingredients and the websites on how to make cocktails being widely available and easily accessible.” Last year the firm’s sales flipped from being 20% off‐trade to 80%‐90%, according to de Heer.

As for the on‐trade, he says: “Personally, I think we will get back to where we were, but it will take some time. Outlets have gone out of business, but there will be new ones starting up, and in the end what I see is that people really want to go out and enjoy a cocktail. I expect the trade will be back to what it was in about two or three years.”

Created for the trade

Emma Fox, vice‐president for Bacardi’s elderflower liqueur St‐Germain, says the brand “has always been a staple of the bartender’s repertoire. It was created for the trade, and was always made to mix.”

The pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns forced a shift to retail and e‐commerce to supply all the amateur mixologists out there. Since the reopening of bars, she says: “People still continue some at‐home hosting and creativity.” She believes consumers have “created their own little rituals, and these won’t go away. At St‐Germain we are seeing much more curiosity, invention and confidence at home.”

At Irish cream liqueur Coole Swan, assistant marketing manager Rachel Moriarty agrees these lockdown rituals are here to stay. “We absolutely see this trend continuing; people love sharing their creations online, and we have seen an increase in people tagging us in their at‐home cocktails since the pandemic,” she says. “Of course, people will start going out again, but we think staying in is the new going out, and people will continue to entertain more at home, and at‐home cocktail making will play a huge role in this.”

In some ways cocktail liqueurs are like members of a backing group, there to support the star on stage, but vulnerable to being replaced. Bacardi’s Fox reckons the solution is to forge your own identity and sense of purpose. “I came into the liqueur category and St‐Germain at the start of the pandemic, and I saw people were looking for inspiration, new drinking experiences and ways to express their creativity,” she says. “If you can provide that for them there’s a genuine role to be played.”

While much of her brand is consumed in a Spritz or Hugo cocktail, veteran orange liqueur Cointreau has been surfing the Margarita wave on both sides of the Atlantic.

“Tequila is booming in the UK; it’s crazy, and it’s the same in France and Australia,” says Fanny Chtromberg, Cointreau’s international brand director. “We benefitted from lockdown. People were confined, they had time and they had money because they weren’t spending outside.” Globally, she reckons that roughly half the brand is being consumed straight, with the rest in cocktails, and that is the part that’s growing. “I’m glad people decided to choose Cointreau instead of other, cheap triple sec because at least if they drink a cocktail, they’ll drink a good one,” she says.

There is still a sizeable after‐dinner market for Cointreau, and in France it enjoyed a spike in sales in late January during religious festival La Chandeleur, when, together with Grande Marnier, it is poured over a few million crêpes and set alight. “We now say we don’t want to be in with the crêpe, we want to go with the crêpe,” explains Chtromberg.

But while she is keen to promote the brand’s mixability, she is more than happy with its heritage status. “The traditional liqueur category is booming, because it’s the main ingredient in over 300 cocktails,” she says. “Instead of a cheap triple sec, with Cointreau people see it’s the same liquid for more than 150 years.”

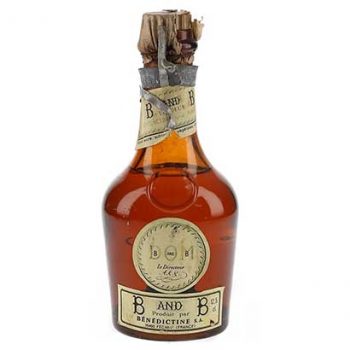

Vintage style

Meanwhile the category has developed a fascinating secondary market on its own. It is still pretty niche, but it is growing, as Isabel Graham‐Yooll, auction and private client director at Whisky.Auction, explains: “I’ve been here since 2016, and I remember we used to hate liqueurs because we wanted to be a specialist whisky auctioneer, but now sometimes we have more liqueurs than anything else.” As a true convert, she says: “What’s astonishing is how spectacular old liqueurs are – that’s the bit that would just explode people’s minds if they knew.”

Chtromberg’s comment about Cointreau never changing is what brand directors invariably say, but as Graham‐Yooll would tell you, it’s not always entirely true. “Some were smaller brands and as they’ve grown, they’ve found more efficient ways of creating similar flavours, so, for instance, natural ingredients have been replaced with artificial ones.”

Sometimes brand owners have been forced to alter the recipe because of a change in the rules on what is allowed to be used.

“If you look at old bottles of Campari in relation to the current release, you can see straight away that they have a very natural colour because they’re less likely to have been made from beetle wings,” Graham‐Yooll says, referring to cochineal. Campari allegedly stopped using this natural red dye from crushed Peruvian insects in 2005, possibly because of consistency issues or veganism, or because bug juice has a low appeal among the squeamish.

Whisky.Auction is seeing plenty of interest in old Campari and in old, full‐strength bottles of Gordon’s gin to satisfy a thirst for one cocktail in particular. “The day you taste a vintage Negroni is something you’ll never come back from,” says Graham‐Yooll. “It’s a different beast. It’s like going for a great meal with very exotic ingredients that have been foraged.” She says this is especially true if the cocktail is built and chilled in the traditional way in a jug and served without ice.

At the 2021 Whisky Show in London, she and her colleagues presented five famous Scotch blends from the past alongside their modern‐day equivalents. “Universally, everyone preferred the older ones,” she says.

“What was interesting was how some were astonishingly different, and some you could actually tell how they’d attempted to keep the style as consistent as possible.” As with all vintage drinks, including liqueurs, she would like the industry to be slightly more open. “Once you start being a bit more honest, it’s not so bad. It’s just a bit more complicated,” she says.

While liqueurs tend to have a lower ABV than spirits, it is their high sugar content of at least 100g/litre that helps preserve them for decades, in the same way that sweet wines typically last longer than dry wines. “And they do evolve over time and become mellow, particularly if they’ve got natural ingredients,” says Graham‐Yooll, who has yet to decline a bottle for being out of condition.

“Although, we don’t accept cream liqueurs into the auction, having seen one too many curdled ones,” she adds. “It kind of curdles the appetite.”

The supply of old liqueurs comes from people clearing out their drinks cupboards or from bars that have closed. “People selling them are very surprised to learn that what they were about to pour down the drain actually has monetary value and is going to be consumed, and not only that, consumed by someone who’s going to be utterly delighted with it,” says Graham‐Yooll. Some will be bartenders who know their drinks inside out, others just ordinary punters who love the thought of mixing themselves a genuine Prohibition‐era cocktail, for example.

There are also collectors for vintage liqueurs such as Chartreuse, as Stuart Ekins, director of Cask Liquid Marketing, the brand’s UK importer, has noticed. In its famous shades of green and yellow, Chartreuse has developed something of a cult following. “I do think there’s a demographic that’s now very much into knowledge and discovery,” he says.

“There’s a certain trust element as well with heritage brands.” Ekins reckons sales were 85%‐90% on‐trade, but with the surge in e‐commerce and with bars reopening, he says: “The actual volumes have really pushed on from where they were pre‐Covid.”

As for how Chartreuse is being consumed at home, Ekins says: “I don’t think people are drinking it neat. If they are they’ve got a fairly strong constitution.” In other words, we’re talking cocktails, which, in all their glorious diversity and innovation, have really helped rescue the liqueurs category. Just think of all those liqueurs languishing in the after‐dinner drinks ghetto, selling only at Christmas, that are now enjoying a whole new lease of life.

Related news

Inside the ‘spiritual home’ of Scotch