Rum producers spring into action against climate change

By Nicola CarruthersThe climate crisis is causing rum producers to take action to ensure the long-term health of sugarcane for their spirits.

*This feature was originally published in the September 2025 issue of The Spirits Business magazine.

Rum’s roots lie in sugarcane and molasses, but the stability of those raw materials is no longer a given. Climate change is reshaping the landscapes that supply the rum industry, with rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, and extreme weather events placing pressure on cane harvests and the availability of molasses. For distillers, that means tighter margins, supply risks, and questions over how to safeguard quality. As the category continues to grow globally, producers are being forced to reckon with climate realities that could redefine the way rum is made, priced, and positioned in the market.

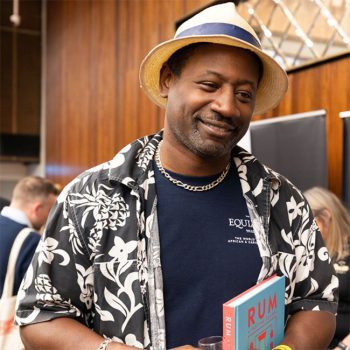

Ian Burrell, founder of the UK’s RumFest, notes the challenge is pinpointing when the ideal time is to harvest sugarcane. He says that sugarcane needs a balance of rain and sunshine, but climate change is disrupting that rhythm. “When you have irregular weather patterns [due to climate change], regular harvesting becomes erratic.”

He explains that the lack of rain or too much of it in one year will affect not only the quality of sugarcane, but the quantity. Producers who make rums with molasses, rather than fresh cane juice, have the benefit of being able to store the product (which can be imported from a country with an abundance of molasses) to ensure there is a back-up supply, Burrell adds.

“We’re seeing that a lot, especially in the Caribbean, where they are bringing in molasses, not only from the Caribbean region, but from far afield, like Asia or Fiji. You can store and transport molasses from one place to another in super-tankers.”

Any change in the weather will have a negative impact on the quality of the cane and the sugar, says Mikey Melrose, head distiller at UK-based V Rum. He notes that it can lead to price increases for molasses but supply remains steady. The company has experimented with UK-grown beet molasses, however if it’s used in production, then the product cannot be legally called rum, as it must be made from cane.

In the Seychelles, family-owned Takamaka produces agricole rum from local sugarcane, and distils rum from Mauritian molasses. When the distillery launched in 2002, cane farming on the islands was limited, and mostly used to make baka, a local cane beer. Today, Takamaka grows seven to nine cane varieties with local farmers on Mahé, using them for its unaged Napa Laz agricole rum. But co-founder Bernard D’Offay notes farmers often work with multiple varieties, complicating production. “We have no option but to import molasses,” he says, “but we’d rather invest in the local cane industry than bypass it to save money.” For now, less than 5% of Takamaka’s rum comes from Seychellois cane.

Certifications are gaining ground as both a sustainability measure and a commercial tool. For Takamaka, it was important that the company’s molasses supply comes from a Bonsucro source – a non-profit organisation that promotes sustainable sugarcane, and runs a certification programme. Extreme weather has affected molasses in Mauritius – last year a major cyclone brought torrential rain and flooding to the Indian Ocean island nation. The cyclone wiped out 20% of the crop, according to Takamaka.

Tim Etherington-Judge, co-founder of Avallen Calvados and sustainability consultancy Avallen Solutions, says an increase in temperature is also affecting sugarcane. “Even though sugarcane grows in tropical areas, it has a band of temperature that it really prefers. In a lot of countries, we’re starting to reach the limits of those boundaries. It grows during the day then produces the sugar at night when it’s cooler. So it requires cool evenings for it to have a high sugar content. As the evenings are getting hotter, it’s reducing the plant’s ability to produce high sugar content. You may still have big, healthy-looking crops, but the sugar content is lower, and with sugarcane, the sugar content is critical.”

To address this issue, Etherington-Judge says the industry must grow sugarcane more sustainably. As an example, he says: “You can grow crops in between the rows of cane. You don’t just have to grow the cane itself. You can grow all sorts of things in between the rows that helps with soil health. Healthy soil absorbs more carbon and reduces waste.”

More local sourcing is another way, Etherington-Judge believes. “What Takamaka is doing is great, sourcing their molasses from Mauritius, which is the nearest major producer, and Mauritius is one of the leaders when it comes to sustainable sugarcane production as well. As an island, they’ve done a lot of work in building resilience into the island because they’re this small island nation in the middle of the Indian Ocean, so very susceptible to cyclones. A cyclone could come in and wipe out almost all of the production.”

He notes the island is susceptible to rising sea levels and the ingress of salt water, which can be detrimental to soil quality. Takamaka is also working to become B Corp- and Bonsucro-certified as a brand, ensuring traceability in the entire supply chain.

Improved conditions

Like Takamaka, Spirited Union also buys Bonsucro-certified molasses to produce its botanical rum. This year, Spirited Union was awarded a Chain of Custody certification by Bonsucro, which proves its commitment to measures that help improve labour conditions on sugarcane farms and in mills.

Founder Ruben Maduro believes demand for Bonsucro-certified rum will only grow, with retailers already prioritising certified brands. “We’re seeing in places like Scandinavia, where you have government-controlled spirits retail, that one of the main criteria for getting on the shelf is being Bonsucro-certified or being a Bonsucro member,” he says.

Takamaka has also noticed demand for these certifications among its export customers, including distributors and bars, where buyers are asking to see a brand’s credentials as part of the pitching process. The firm notes one major hotel group in Dubai as an example, alongside Scandinavia’s off-trade.

Etherington-Judge says certifications like Bonsucro and B Corp are “valuable commercially”, and provide buyers with a “very quick and easy decision” when it comes to choosing products to stock.

Burrell has also pointed out how the impact of major weather events like hurricanes not only affect sugarcane crop but other important elements for a distillery, such as electricity. As an example, he highlights Foursquare in Barbados, which is “one of the most popular rums at the moment, and will have allocations of rum to make for various clients. Now, if a hurricane knocks out electricity on that island, then that sets them back.” He adds that not every company has the “luxury of a solar panel or renewable sources of energy”.

Burrell believes there are unique challenges to operating on an island that other countries such as England or France do not have. “If your power goes down, or the internet is down, then you can’t communicate with your suppliers for 24 hours,” he gives as an example.

There are also some distilleries that have revived sugarcane production in their countries, and are working to safeguard the crop in the future. Hawaii’s Kō Hana Distillers has taken this approach, launching initially in 2009 as a farm, and becoming a leader in preserving native sugarcane varieties. Once a major global sugar producer for more than a century, the state’s last large commercial sugar plantation closed in 2016. For its rum, Kō Hana grows more than 30 heirloom varieties of sugarcane on the island, which are difficult to find. The company makes single-variety rums, and the aim is to eventually have a flagship range.

“One of the harder things we have to do is just keeping the seed alive,” says farm manager Jakob Dewald. “It’s something that’s a lot more challenging with these canes – they’re a little more fragile, and you find them in different places. Travelling to different islands and trying to find these cultivars and working with other research centres to try to get some that no one’s had or seen for decades has been really challenging. Even when we’re growing these canes, they’re not as resilient as some of the more high-production ones – they can take a lot more abuse. You have to really baby these ones in some instances.” The company continues to actively search and find other varieties, as “there’s always a need for more”, he adds.

Kō Hana is also aiming to regenerate a lot of the soil it uses. “Most of what we do is regenerative,” Dewald explains. “If we look at how we grow cane compared with other producers, we don’t till our land for at least five years. That is the minimum. We harvest the cane and let it regrow, which you don’t traditionally see, especially in any sugarcane production – they’ll just harvest in a year or sometimes two, depending on whether they’re in a more tropical area. That’s something we don’t do, we just let the canes regrow naturally.”

Dewald says some varieties grow better than others, which can depend on their genetics and where they’re grown. “In higher elevations where it’s a little bit cooler, some canes do a lot better than canes that like the lower elevation and a lot of heat. We’re trying to figure out which does best where.”

The company is hoping to preserve its various sugarcane varieties for future generations. “We want to be that resource for other people to come and take those seeds from us,” he adds. “Even if they don’t do great for rum making or even production in general, if we can be a part of preserving culture, that’s something that, as a company, is really important.”

Kō Hana has also thought ahead and prepared itself in case a disaster happens and wipes out any of its sugarcane varieties. “We have multiple gardens where we keep these varietals, and there are also some collections and areas that we definitely know where they are. So if some crazy catastrophe happened, whether it’s a fire or disease that was to run through a different garden, we know where to find these canes, so we know where and how to keep them alive. We do keep them in different fields, different areas, just to be sure that if something does happen, we can always bring them back quickly.”

With some countries experiencing weather warmer than usual due to climate change, could there be more areas with the capability to grow their own sugarcane?

Burrell ponders: “If you ask a wine expert, they’ll tell you yes, that it has helped with vines and grapes,” allowing the UK to grow some good-quality wine. “Who knows in the future? I was involved with a geothermal rum distillery that was using waste heat to create and generate power to run a still,” he says, pointing to the Cornish Geothermal Distillery Company, a project in the UK that received funding from the government in 2021. “The initial idea was to use that heat to power and create an artificial tropical climate in a biome to grow sugarcane. That project is still ongoing, but it’s run out of funding.”

Burrell sees renewable energy as one of the few real ways to counter climate threats. He notes many distilleries, like Takamaka, are using solar panels to generate energy, and some are even looking to sea waves as an energy source. He adds: “Any way to save on your carbon footprint is going to be a positive thing for the rum industry.”

As climate pressures reshape the sugarcane supply chain, rum’s longevity depends on how well the industry adapts. Producers are already turning to regenerative farming, renewable energy and smarter sourcing, proving resilience is possible.

The sharing of knowledge and resources may be the key to safeguarding rum’s future – and ensuring the spirit continues to thrive for decades to come.

Industry insights

How could climate change shape the rum industry over the next 10 to 20 years? How do you prepare for the future?

Alexandre Gabriel – master blender and proprietor, Maison Ferrand and Stades Rum Distillery

“Climate change is already having an impact on our rum production in the Caribbean, and this will intensify over the next 10 to 20 years. We’ve observed an increase in average temperatures of nearly 1°C since the 1960s, and projections indicate a further 1.5°C-2°C by 2050. This is changing the physiology of sugarcane, which is suffering from warmer nights and longer droughts, with episodes of brutal rain. As for ageing, heat increases the angels’ share, which has increased from 7%-8% per year historically to now 9%-10% in some cellars. This is major. The reduction in the day-night temperature range also limits the expansion and contraction cycles of the wood, changing the extraction and balance of aromas. In Barbados, we are developing cane varieties that are more resistant to heat and drought. We’re also adapting our ageing practices, exploring more ventilated cellars, barrels with varying profiles, specific wooden vats, and loss-management methods.”

David Palacios Jaramillo – global PR manager, emerging brands, Brown-Forman

“Climate change will undoubtedly reshape not only the rum industry but the entire spirits sector and beyond. At Brown-Forman, we are deeply committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, protecting water resources, minimising the environmental impact of our packaging, promoting sustainable agriculture, and supporting forest conservation. These efforts are central to our long-term strategy and responsibility as producers.”

Filippo Maria Olivi Di Briana – CEO, El Supremo Rum

“Climate change is reshaping the global rum industry, particularly in sugarcane cultivation. While many regions face rising temperatures and erratic rainfall, Paraguay offers a unique advantage. Our landlocked position with very fertile soil and a temperate climate provides a buffer against extreme weather events, creating a stable environment for agriculture. Additionally, the Guaraní Aquifer, the world’s second-largest freshwater reserve, supplies us with some of the purest water available. To further enhance sustainability, El Supremo and Capasa distillery collaborate with local farmers on reforestation initiatives, including the planting of eucalyptus trees. These efforts aim to improve soil health, increase water retention, and support biodiversity in the Gran Chaco biome, ensuring the long-term viability of our production practices.”

Marjon de Haan – chief procurement officer, E&A Scheer

“Over the next 10 to 20 years, climate change will impact the rum industry by altering sugarcane-growing conditions and intensifying supply chain volatility. Rising temperatures and unpredictable rainfall may impact crop yields and fermentation dynamics, while extreme weather changes could disrupt logistics and ageing environments. As a bulk rum supplier, we’re proactively investing in resilient sourcing partnerships across diverse geographies, adopting sustainable production practices such as Bonsucro-certified rum. Our commitment is to take responsibility in the supply chain and together become future-proof.”

Yannick Noel – rum business unit manager, Grays

“Climate change is shaping the rum industry in terms of procurement of raw material, as sugarcanes are very sensitive to it. Drought results in lower cane stems, so less cane-juice extraction, which creates a scarcity of raw material for distilleries. To prepare for the future, the idea is to emphasise quality over quantity: to move toward products with more added value to compensate for volume decline. It is also necessary to strengthen the ‘terroir and authenticity’ message in an unstable climate. To this end, we are actively working on developing a geographical indication as part of a strategy to promote the terroir and its unique characteristics, positioning Mauritius as a key player in the rum sector. The decline in sugarcane production is weakening the rum industry in the short term but is pushing the Mauritian industry towards an upmarket approach, better promotion of the terroir, and sustainability.”

Marie Benech – communications, public affairs and CSR director, Havana Club

“At Havana Club, our terroir is our home, where our rum was born and is still made today, using 100% Cuban sugarcane. That’s why preparing for the future and ensuring that Cuban sugarcane will remain at the heart of our rum for generations to come is not optional – it is integral. Sustainability is second nature to Cubans as they’re dab hands at mending, reusing, and repurposing. It is our responsibility to ensure Havana Club respects its island home and the values of today’s consumers. An example is the EcoPlant installed at our San José distillery, enabling closed-loop distribution of rums to some on-trade venues on the island, which reduces bottle imports, glass waste, and carbon emissions related to packaging. Also, more than 5,000 solar panels are installed at our distillery, which covers 75% of our daily electricity needs, with excess energy redistributed to local communities at no cost.”

What challenges do you face producing rum in a country not traditionally associated with it?

Graham Appleyard – CEO, DropWorks Distillery

“People don’t always associate quality rum production with Britain, unfortunately, but as soon as I mention Scotch, then the penny usually drops. The same weather that’s been brilliant for whisky is brilliant for rum too. There’s been plenty said about tropical versus non-tropical ageing, but Britain has its own distinct advantages. The natural variations in our temperate, maritime climate encourage the casks to breathe and interact with the spirit, building layers of flavour. At the same time, the cooler conditions in our cow sheds and soon-to-come tunnels give us the opportunity to slow maturation down when we want to, creating real depth and character. So although Britain isn’t tropical, it’s not necessarily a drawback. It allows us to create an even wider range of flavour.”

How do toasting and charring levels influence the flavour profile of rum?

Boris Stawski – sales and marketing, NAO Oak

“Toasting and charring define the rum’s aromatic architecture. Gentle to medium toasts unlock caramel, vanilla, and sweet spice, while deeper toasts bring cocoa, coffee, and roasted nuts. Charring adds a charcoal layer that polishes the spirit and enhancing molasses, toffee, and smoky depth. We can also create elegant combinations, pairing toasted or charred staves with fresh, untoasted new wood heads, to preserve brightness, freshness, and length. And while we talk about toasting levels, the real magic happens when these profiles are matched to the right oak species or other wood types, ensuring perfect synergy between wood and spirit.”

Related news

Goslings Rum appoints new UK distributor