Research shows terroir in whisky does exist

A study led by Oregon State University and Waterford Distillery has concluded terroir does have an impact on the flavour of whisky.

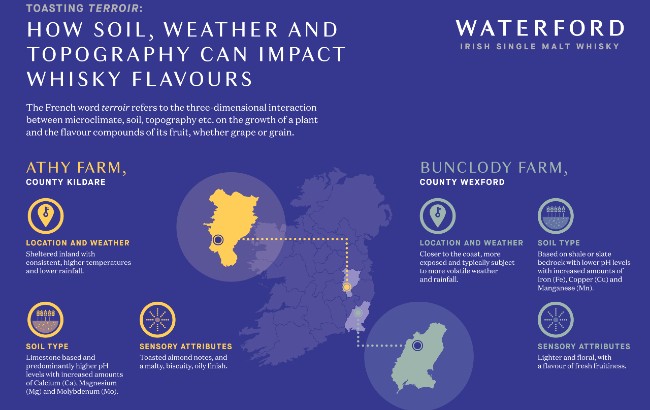

Terroir is the French notion that environmental conditions such as soil, weather and habitats can affect flavour.

A peer-reviewed academic study, published in scientific journal Foods, which was driven by Irish whiskey producer Waterford Distillery, shows terroir can be found in barley and the single malt whisky made from the grain.

This is the first paper from The Whisky Terroir Project. Research was conducted by an international team of academics from the US, Scotland, Greece, Belgium and Ireland, including: professor Kieran Kilcawley and Maria Kyraleou, of Teagasc Food Research Centre, part of the Irish Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine; Enterprise Ireland; Minch Malt; and featured cooperation from Scotland’s leading whisky laboratory.

Dr Dustin Herb, lead researcher and post-doctoral research at Oregon State University, said: “This interdisciplinary study investigated the basis of terroir by examining the genetic, physiological and metabolic mechanisms of barley contributing to whisky flavour.

“Using standardised malting and distillation protocols, we preserved distinct flavours associated with the testing environments and observed year-to-year variations, indicating that terroir is a significant contributor to whisky flavour.”

The study analysed two barley varieties, olympus and laureate, grown on two farms with different environments in 2017 and 2018 – Athy, County Kildare, and Bunclody, County Wexford, Ireland.

Each barley sample was micro-malted and micro-distilled in laboratory conditions to create 32 different whisky distillate samples.

The samples were then tested by lab analysts using gas chromatography – mass spectrometry – olfactometry (GC/MS-O), alongside sensory experts.

The research showed more than 42 different flavour compounds, half of which were ‘directly influenced’ by the barley’s terroir.

Kilcawley, principal research officer at Teagasc, said: “We utilised gas chromatography olfactometry, which enabled us to discern the most important volatile aroma compounds that impacted sensory perception of the new make spirit. This research not only highlights the importance of terroir, but also enhances our knowledge of key aroma compounds in whisky.”

Athy, which is a more sheltered, inland area, had higher pH levels and greater traces of calcium, magnesium and molybdenum in its limestone-based soil. Furthermore, the area had consistent, higher temperatures and lower rainfall. New make spirit distilled from this barley was found to taste of toasted almonds, with a malty, biscuit-like, oily finish.

Meanwhile, the Bunclody farm had lower pH levels and higher amounts of iron, copper and manganese in the soil, which was located on a shale or slate bedrock. As it was closer to the coast, the weather at Bunclody is more unpredictable compared with Athy. Typical tasting notes from new make spirit made with this barley included a lighter, floral style, with fresh fruitiness.

Researchers believe the findings of the study are significant because it creates the possibility of producing region-specific whiskies in the same way as wine, and could lead to an appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC).

Mark Reynier, founder and CEO of Waterford, said: “Barley is what makes single malt whisky the most flavoursome spirit in the world. This study proves that barley’s flavours are influenced by where it is grown, meaning – like wine and Cognac – whisky’s taste is terroir-driven.

“Critics claimed any terroir effect would be destroyed by the whisky-making process, saying there is no scientific evidence to prove that terroir even exists. Well, now there is.”

The next part of the project will examine the same role of terroir in whisky using analysis based on Waterford Distillery’s own commercial spirit and matured whiskey. The results are expected to be published in 2022

Conditions of the experiment

Olympus and laureate barley varieties were grown at Athy and Bunclody, and harvested over two consecutive seasons from 2017 to 2018.

Both trials were sown in ‘randomised’ complete block designs from 19-22 March and 27-30 April, in 2017 and 2018 respectively.

In 2017, the barley crops were harvested on 15 August in Bunclody and 31 August in Athy. The following year, the crops were harvested on 8 and 10 August.

Sowing and harvesting of the crops, and micro-malting of the barley, was conducted by Minch Malt in Ireland. Samples of 16kg were micro-malted following the malting protocol steeping at specific times and temperatures.

Mashing and distillation of the malted barley was carried out by Tatlock and Thomson in Scotland.

Around 10kg of each sample was ground in a lab with a three-roller mill. The malt grist was mashed with 28l of hot water (65oC) and then with 14l of hot water at 85oC in a lab mash tun.

The water from each mashing was drained, mixed, and around 28l of wort was collected. The wort was then fermented using anchor dried distilling yeast for 72 hours, at 32.5oC. After fermentation, the wash was distilled in a lab spirit still to no more than 76% ABV.

When it came to the gas chromatography olfactometry (GCO) sessions, panellists were asked to avoid very spicy meals, smoking and coffee at least one hour before nosing, and not to wear perfume or strong deodorants. The olfactory tests were carried out by six trained panellists, comprising two men and four women.

Statistical analysis was conducted with JMP Pro statistical software. A mixed linear approach was used to analyse the sensory data.

In conclusion, the study said: “This study has clearly demonstrated variations in the contribution of the aroma active volatiles and sensory attributes in these new make spirits, and reflects changes in barley growth in relation to environmental elements including soil nutrients and prevailing seasonal weather patterns, and therefore reveals a “terroir” effect.

“Further research is required to better understand the specific environmental impact on barley growth and the management and processing thereof with respect to the genetic, physiological, and metabolic mechanisms contributing to the terroir expression of new make spirit and whisk(e)y.”